If you referred to Patric McCoy as merely a photographer, he would promptly set you straight—despite having taken countless photos that earned him four exhibitions, caught the attention of Los Angeles’ Getty Museum, and potentially led to an upcoming book deal.

During an exclusive interview with solusikaki.com McCoy recounts the tales behind his famous photographs and presents us with some images displayed in galleries along with others never showcased previously.

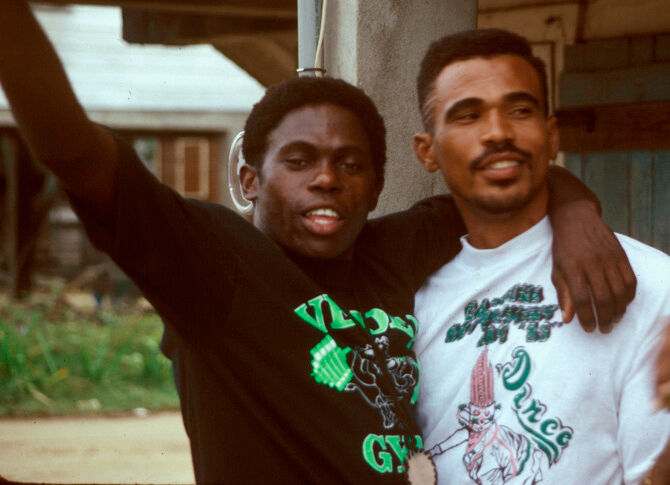

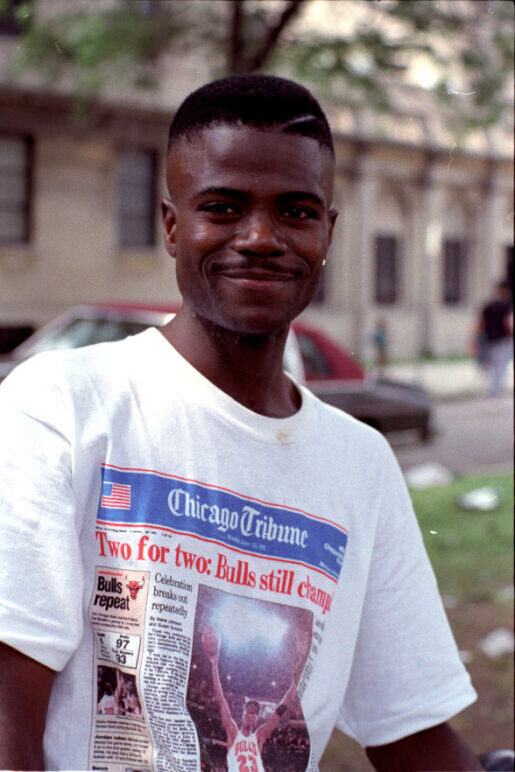

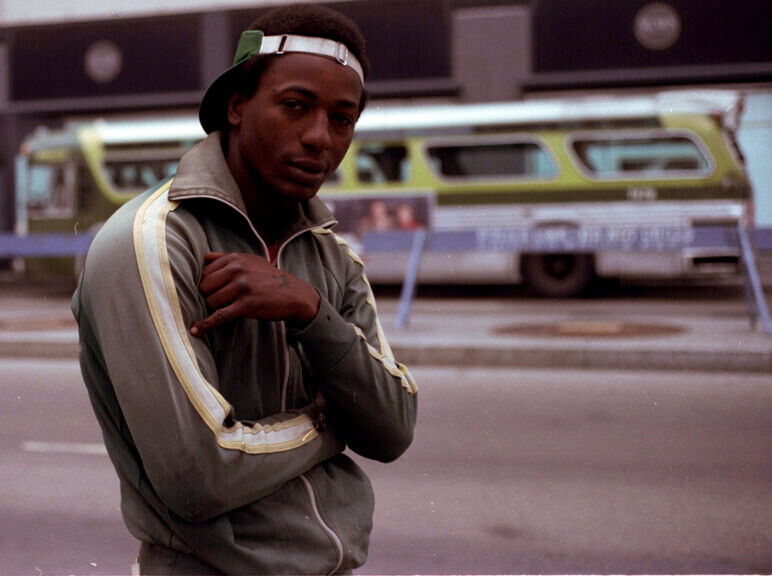

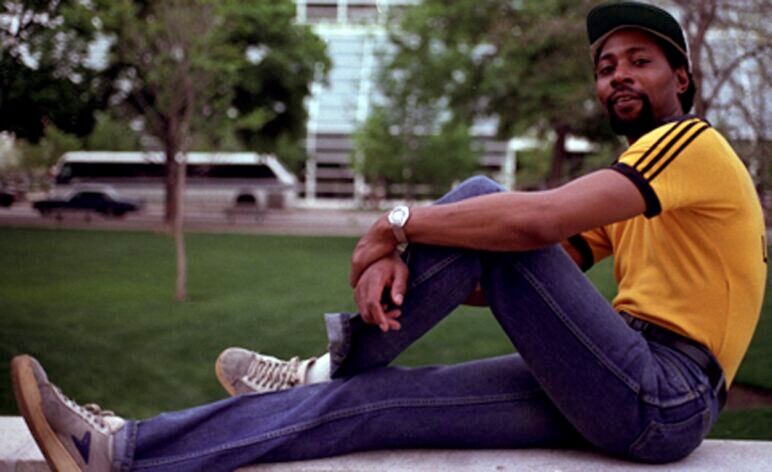

McCoy indicates it's more precise to state he was a photographer During the 1980s, McCoy journeyed through his hometown area of Chicago’s South Side, capturing candid images of people he knew as well as those he met along the way. This body of work grew into tens of thousands of unstaged snapshots offering a personal glimpse into the lives of Chicago’s African American LGBTQ+ population during the era marked by economic policies under Reaganomics, the emergence of house music, and the devastating impact of the AIDS epidemic.

In the 1970s, McCoy initially became interested in photography, utilizing a basic point-and-shoot camera to capture images of his immediate family members and acquaintances, with many being fellow African American homosexual males.

They sort of served as a secretive record of an alternative existence," explains McCoy. "These photos weren't meant for the average audience, despite them being neither explicit nor provocative. The reason was simply that I preferred keeping my professional activities under wraps.

Back in 1984, when McCoy was 38 years old, he made the switch from using a basic camera to one capable of handling 35-millimeter film. Instead of enrolling in courses or seeking advice from either his father or brother—both passionate about photography—he opted to learn everything on his own through firsthand experience. To keep himself motivated, he penned this resolve onto a piece of paper: For an entire year, he vowed always to have his camera with him; should someone request a photograph, he promised not to refuse them.

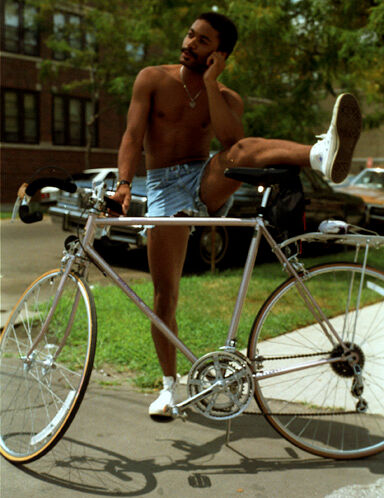

A single year extended to half a decade. Regardless of the weather, every day found him cycling from his residential area to the central offices of the Environmental Protection Agency located downtown. He served as an environmental scientist at the agency for 29 years.

I look like a total nerd on a bike with a camera dangling from my neck, unaware that this would become a signal for people to ask me to photograph them. Due to my dedication, I found myself having to go through with it.

What McCoy wasn't aware of at the time was that he was documenting a crucial period for Chicago’s African American and LGBTQ+ communities. As he cycled daily through predominantly Black areas on his way to work, these neighborhoods were suffering greatly due to a mix of economic policies under Reaganomics along with stringent criminal justice measures that pushed numerous Black individuals, mostly men, into unemployment or incarceration.

McCoy notes that this led to a surge in homelessness among Chicago’s Black population, a situation few had anticipated. As people started establishing makeshift settlements and tent cities in the Loop and South Loop areas, these regions swiftly gained notoriety as places where one could find illicit activities such as drug deals and prostitution.

It was also the latter part of the sexual The revolution and the formative period of Chicago house music took place during warehouse events in the South Loop. It gained significant traction within the city’s Black LGBTQ+ community.

There existed an evident clandestine sexual subculture where individuals would signal you or offer subtle indications to convey their availability and interest. This aspect was part of the milieu I found myself navigating.

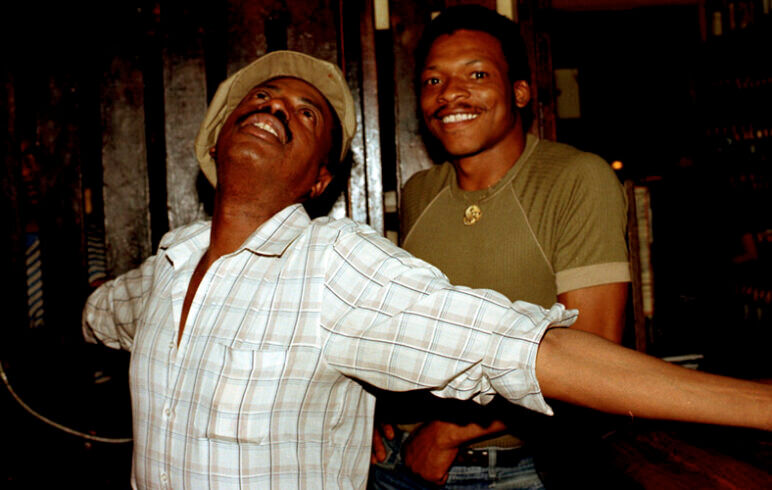

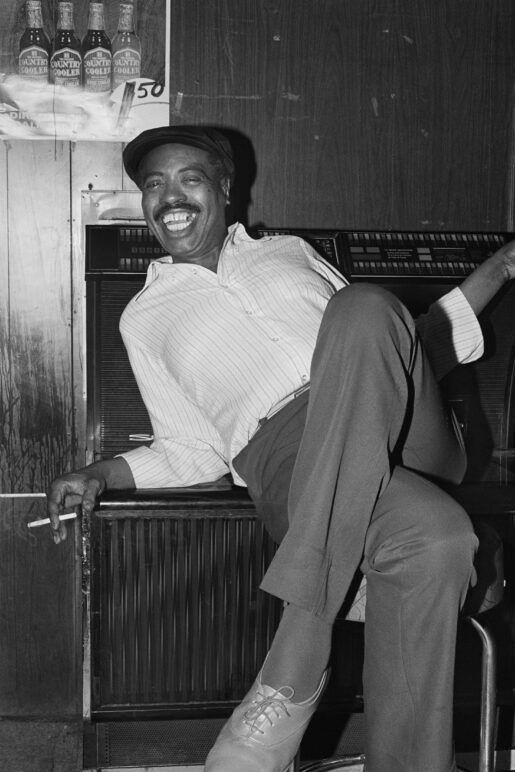

Amidst the chaotic hubbub of 1980s Chicago stood the Rialto Tap, a gay establishment in the Loop frequented by McCoy for numerous photo sessions. This venue drew an eclectic mix of African American gay individuals and those who identified as "down low," along with drag queens and transgender women—groups largely unwelcome in most of the city’s other gay bars during that era.

That used to be my place," McCoy recalled about the closed-down Rialto. "It was just a short walk from where I worked, and it felt completely different. One moment I'm in an official government office handling serious tasks, then a mere block away, there was a hub of debauchery. But I adored every bit of it.

Back in the day, the Rialitoften faced police raids because dressing in a way that didn’t conform to one’s assigned gender or dancing with someone of the same gender could lead to arrest. This wasn't even considering the issue with drugs, as mentioned by McCoy.

When law enforcement entered and instructed everyone to exit through the back door, it resembled a pharmacy. Various drugs were scattered across the floor, yet no one faced arrest during those instances. I've been told that during earlier raids at the Rialot, they used to bring in paddy wagons to fill them with detainees.

McCoy’s latest exhibition, titled "Make MeVisible," was showcased at the Chicago Cultural Center. The collection included 17 portraits, largely shot around the area near the Rialto Theater. According to McCoy, each portrait subtly references 1980s LGBTQ+ culture.

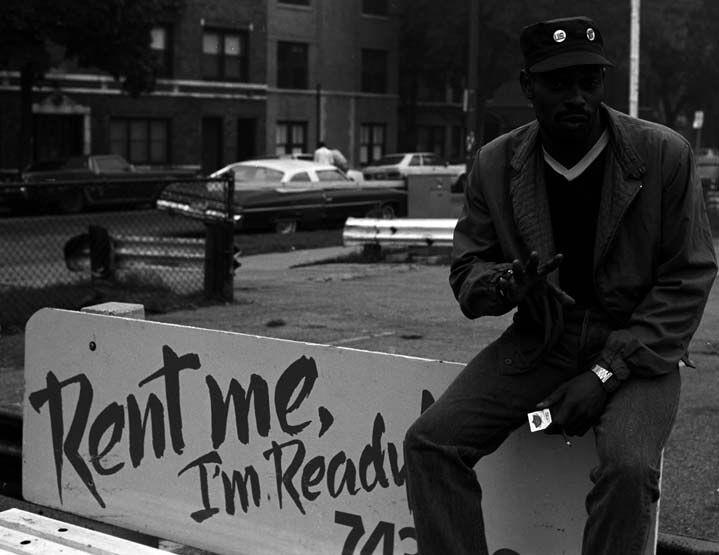

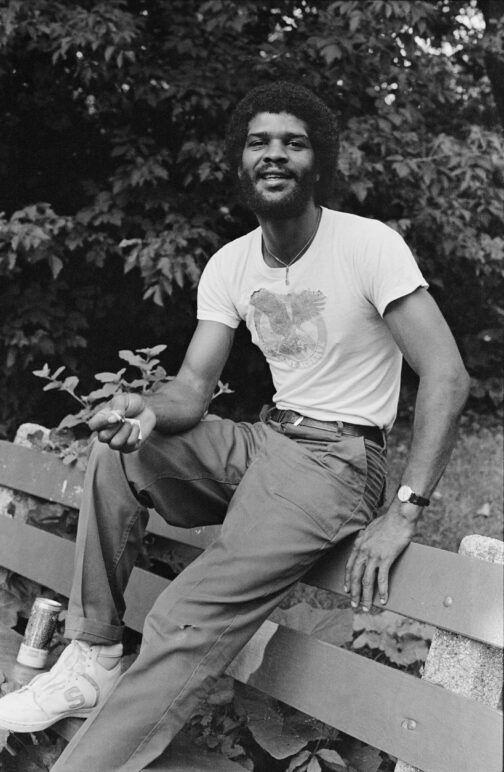

In an image called "Park Cruising," a guy dressed in jeans and a T-shirt is seen sitting atop the backrest of a park bench, with a marijuana cigarette held loosely in his fingers. McCoy explains that the fellow's posture on the bench indicated he wanted to engage in conversation. Many times, requesting a photograph from someone was just a clever way to initiate contact, as per him.

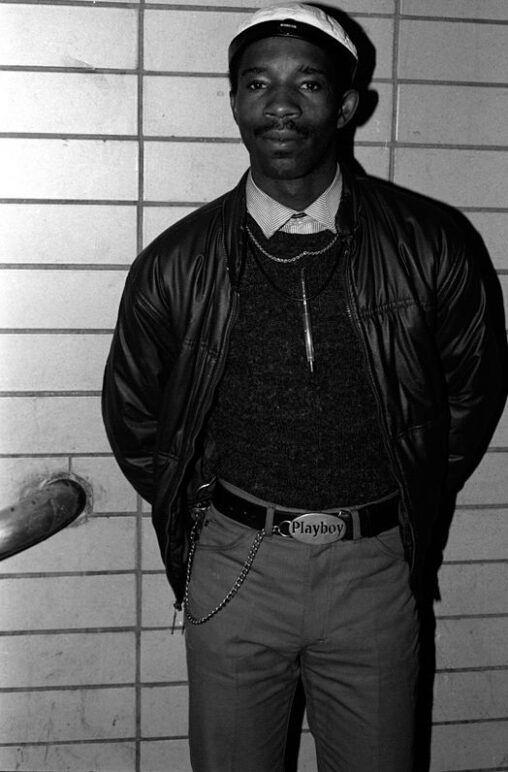

In an additional picture, a gentleman adorned with a leather jacket over a sweater sports a gleaming belt buckle prominently displaying the term "Playboy." McCoy mentions that such belt buckles were frequently used by men as indicators of their interests. There is another image not included in the exhibition where McCoy’s model bears a buckle inscribed solely with “ dick .”

McCoy's collection was exhibited for the first time in 2023 at Wrightwood 659’s “ Take My Picture Since then, his work has been featured at Chicago’s Lyric Opera as part of their exhibit. concrete, rose exhibition and Blanc Gallery's display At First Glance He recently got a call from the Getty Museum in Los Angeles inviting him to incorporate his archive into their collection. His photographs will also be showcased alongside those of other LGBTQ+ artists at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s forthcoming exhibition. Urban Oasis: Queer Art and Activism in Chicago He is currently working on an exhibition. Additionally, he is compiling a catalog for his upcoming Wrightwood show with the aim of transforming it into a future publication.

McCoy is delighted by the revived interest in his photography, although he feels a bit astonished as well.

I'm proud that these works resonate with the LGBTQ+ community of today. We weren't seen this way back then, but I'm glad it serves as a historic touchstone for them now.

When I reflect on those photographs now, I realize how much society has impacted Black individuals," explains McCoy. "Whenever they got an opportunity to be noticed, they desired visibility and documentation." He continues, "It remains unclear to me why random people would request me to photograph them without asking about the fate of the pictures—how they could retrieve them or what the costs might be. It seems like there’s a complex psychological aspect at play; perhaps all they truly craved was acknowledgment.

McCoy’s photographs will be featured in July at the exhibition "City in a Garden: Queer Art and Activism in Chicago" at the Museum of Contemporary Art.